What is Bhavacakra – Tibetan Wheel of Life?

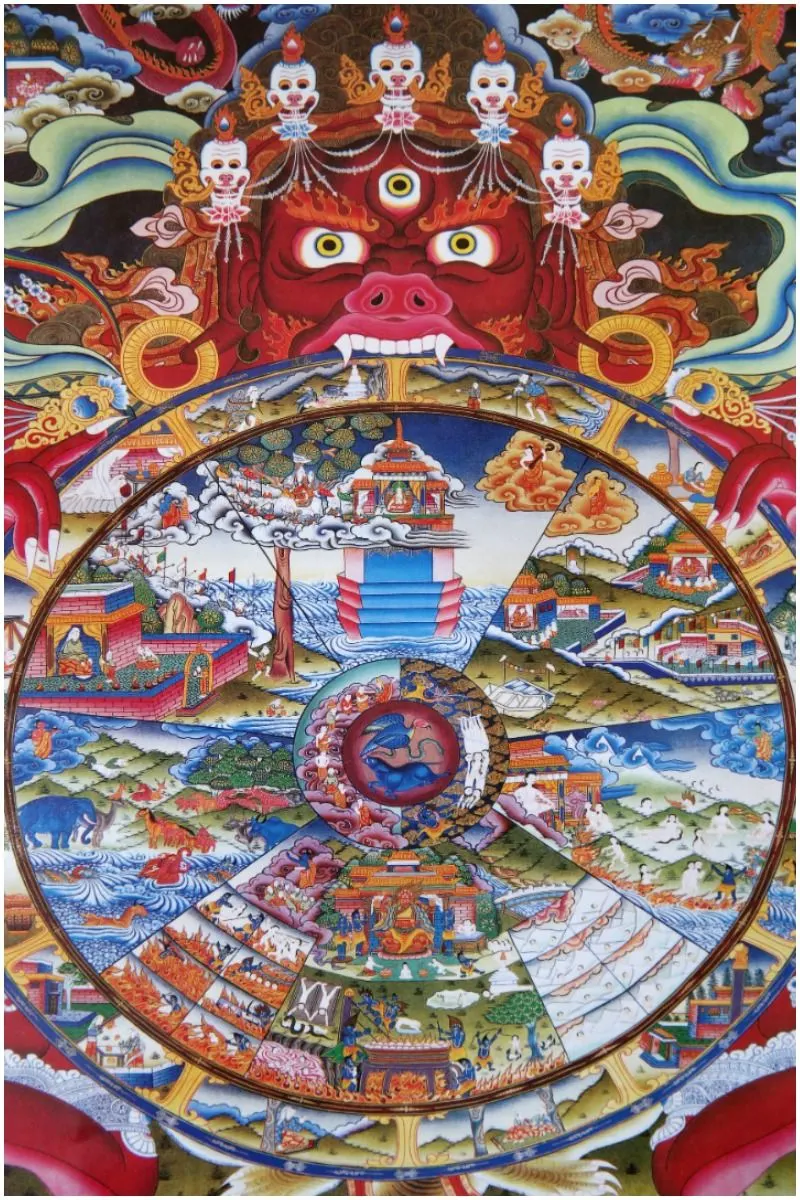

At the doorway to most Tibetan gompas, there is a large fresco of the Wheel of Life (the term is also translated as wheel of becoming or wheel of cyclic existence), which is a great painting signifying Samsara as the plaything of delusion.

In Mahayana Buddhism, it is believed that the drawing was outlined by the Gautama Buddha himself in order to help normal people understand Buddhist teachings.

”One of the reasons why the bhavacakra was pictured outside the monasteries and on the walls (and was really encouraged even by the Buddha himself) was to teach this important Buddhist philosophy of life and perception to more simple-minded farmers or cowherds. – Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche’s quote.

In the center of the wheel are 3 creatures:

- a cock, signifying craving and greed;

- a snake, signifying wrath and passion;

- a pig, signifying ignorance and delusion.

These 3 creatures represent: craving, wrath, and ignorance are the three fires of evil that make sentient beings the victims of Avidya – primordial delusion.

Around them is a narrow circle, half of which is loaded with happy-looking but rather worldly people going up, and half with naked wretches falling down.

As a result of relative victories or defeats in their contest with the ego, sentient beings rise or fall within Samsara’s round, any rise being accomplished by a fall if negative Karma is acquired in the new existence, and each fall being succeeded by a rise when the evil Karma is worked off or if the being acquires merit. All these beings endlessly revolve among the 6 states.

Then come 6 segments of the circle representing the 6 states of existence separately (Gods, Asuras, humans, animals, hungry ghosts, and denizens of hell) or 5 segments, with the first 2 orders in the upper and lower parts of the same one.

The rim is divided into 12 sections, each with a picture signifying one of the links in the twelvefold chain of causality, through which beings are ensnared in life afterlife.

The 12 links in the chain of causation (Pratitya-samutpada) are illustrated in slightly different ways by different artists, but generally, they are as follows:

- A blind man – Primordial ignorance.

- A potter – Fashioning: ignorance giving rise to elemental impulses.

- A monkey playing with a peach – Tasting good and evil: impulses, giving rise to consciousness.

- Two men in a boat – Personality: consciousness giving rise to name and form.

- Six empty houses – 6 senses (including mind): personality giving rise to sense perception.

- Love-making – Contact: the senses giving rise to the desire for contact with their objects.

- Blinded by arrows in both eyes – Feelings of pleasure and pain: contact giving rise to blind feeling.

- Drinking – Thirst: feeling giving rise to a thirst for more.

- A monkey snatching fruit – Appropriation: thirst giving rise to grasping.

- A pregnant woman – Becoming: grasping giving rise to the continuity of existence.

- Childbirth – Birth: birth giving rise to rebirth.

- A corpse – Decay: rebirth giving rise to renewed death and further rounds of birth and death forever and ever.

The entire wheel is in the grasp of a huge and hideous demon who resembles Yama the Lord of Death and wears 5 skulls upon his crown. Yama, Lord of Death, represents Avidya, with the entire universe in its clutch.

Merely rising from one state to another, even though it be to the heavenly bliss of the gods (Devas), brings no release from delusion’s grasp; sooner or later, the gods will tumble back into the more unsatisfactory states – no permanent gain accrues from utilizing merit to procure a positive rebirth.

The 5 skulls in Yama’s headdress represent the 5 senses, the 5 illusory perceptions, the 5 kinds of wrongdoing, the 5 aggregates of being – the very opposites of all that is personified by the 5 Jinas at the core of the mandala.

Near the top of the picture stands the Buddha indicating not at the Wheel of Life, but at another more simple and very beautiful wheel with 8 spokes (Asoka’s wheel), which, for more than 2000 years, has been a symbol of the Dharma, i.e., the Doctrine of the Buddha, and in another sense, Universal Law.

The Buddha points to a proper understanding of the Doctrine and conformance with Universal Law as the best way to Liberation. Sentient beings have a choice between eons of suffering and Nirvana’s bliss, the fruit of Enlightenment.

Among the numerous lessons to be learned from contemplating this symbol is the futility of piling up good works without making a genuine spiritual advance.

Good works at best qualify people for transient joys in the highest of the 6 states of existence, where they are still subject to Dukha, even if it is in the form of general dissatisfaction rather than acute suffering.

Heaven offers no permanent way out of Dukha in its severest forms.

Moral action is admirable in itself; it benefits both the practitioner and recipient, but it does not lead to the conquest of delusion. If the benefits of a virtuous life are to be lasting, there must be a shift of consciousness that goes far beyond morality and piety.

Images credit – @Getty

READ THIS NEXT: What Happens After Death in Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam and Christianity

Lama Surya Das

Friday 30th of October 2015

One of the benefits of the Tibetan prayer wheel is that it embodies all the actions of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas of the 10 directions. To benefit sentient beings, the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas manifest in the Tibetan prayer wheel to purify all our negative karma and obscurations, and to cause us to actualize the realizations of the path to enlightenment.